The article below was reproduced courtesy of the Stefan Batory Foundation.

“At first, I couldn’t even find the toilet because I didn’t know that a circle on the door stood for ‘ladies’ and a triangle for ‘gents’. I couldn’t figure out which room the class was at or that I was supposed to bring separate sports clothes and shoes for the PE class,” explains YiQi, a 2nd grade student in middle school.

YiQi travelled with her parents from China to Poland five years ago and enrolled in the primary school in the community of Mroków without understanding a single word of Polish. Today, she speaks fluently about her first few weeks in the new country and how to survive in a world where everything is different.

School in Mroków

The local school in Mroków is very special. Ten percent of its students are of Chinese or Vietnamese origin. This is largely explained by its proximity to Wólka Kossowska, a home to a major wholesale hub that employs people from China and Vietnam. Minority integration and students support projects have been available in the community for several years. However, many Chinese and Vietnamese students still do not speak Polish one or two years after they start attending Polish schools.

“Foreign children are required to study all subjects in Polish right away. Biology, history, geography – all in a language that is totally incomprehensible to them. I recently spoke to one parent whose child will be held back for the third time. This means that the boy has been stuck in the third grade in middle school ever since he arrived in Poland,” explains Michalina Jarmuż from the World within Reach Foundation.

Jarmuż , who runs the 'Polish Phrasebook' project in Mroków since October 2014, adds that the language is not the only challenge faced by immigrant children in Polish schools.

“I helped one Chinese boy with his maths homework once. The task was to develop a mathematical formula and work with the calendar. Nothing special, you’d think. The thing is, Poland and China have different calendars. So I first had to tell him about the Polish calendar, how many days it has and how you can structure them,” she explains.

“The cultural context is noticeable in all subjects. Additionally, some science problems also have narrative descriptions. Together, the cultural and linguistic hurdles can form an insuperable barrier.”

Foreigner in a Polish School

According to Polish legislation, a foreign child who stays in Poland is obliged to attend school. In addition, children of foreign descent have the right to additional five hours of Polish classes per week. These five hours of language classes a week seem to be a sufficient support for young migrants to pick up the language. The trouble is that these language classes are organised after the mandatory subject-matter classes.

“These kids have psychosomatic symptoms after a whole day of listening to instruction in a language they do not understand – they have headaches and abdominal pains. As laconic as it may sound, the school nurse has confirmed they exhibit all the symptoms of anxiety and culture shock. Learning in such a state is extremely difficult,” says Jarmuż adding that this is often coupled with simple fatigue and frustration of knowing that all the other classmates are either long gone home or playing outside.

Solutions

Other countries in Europe where migrant populations are much higher than in Poland have long implemented policies to help young foreigners adapt to the local school environment. In Norway, where migrants account for 15 % of the population, young students who speak other languages than Norwegian enjoy the right to additional language learning until they are ready to attend regular classes at school.

“Students have the right to learn in their native language or in both languages. This approach applies to children who recently arrived in Norway and children who have limited Norwegian language skills because of their foreign descent. Likewise, students can choose their native language as an additional foreign language in secondary schools,” says Dag Fjæstad of the Norwegian National Centre for Multicultural Education, who was invited by the Polish Children and Youth Foundation to attend a seminar for organisations implementing youth and anti-discrimination projects in the framework of the Citizens for Democracy program.

Poland has made positive step towards the Nordic approach by introducing a transition period for students to learn the language before they begin regular education.

“I myself attended a Polish school with French as the language of instruction. We spent the first year essentially learning French for 20 hours a week. After that year, we were truly prepared to study all other subjects in the language,” recalls Aleksandra Ośko, President of the World within Reach Foundation.

However, schools like the one in Mroków are still relatively rare. The total migrant student population in Poland is at one percent, which means it is not seen as priority. In some instances the authorities even fail to recognise the need at all. However, municipalities and schools facing the challenge appear to be patching the holes in the system by engaging with NGOs.

Polish Phrasebook

The 'Polish Phrasebook' is an example of such cooperation. The project is implemented in the school in Mroków by the STEP Education and Progress Association in partnership with the World within Reach Foundation and Project: Poland.

Any type of support and assistance is important whenever young immigrants arrive to a Polish school.

“The first few weeks were very hard. I was lucky to find a friend quickly, a Polish girl. First, we communicated through drawings. I would draw things and she would tell me what these things were in Polish. Surely, a phrasebook with basic Polish phrases, a survival dictionary of sorts, would have helped initially,” concludes YiQi.

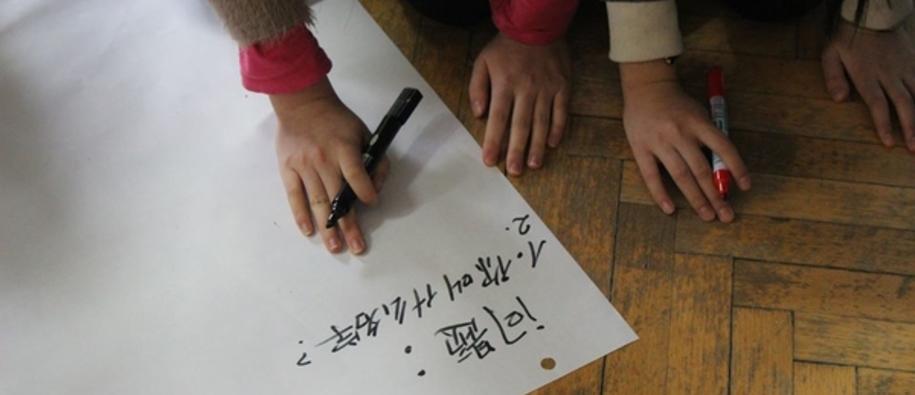

During a winter holiday workshop organised at the school in Mroków, young Polish, Vietnamese and Chinese students worked with photographer Marta Kotlarska to develop pinhole photography skills. They then used their photographs to produce a picture game that helps students learn basic Polish.

“We selected over 20 key sentences to help new students get by. We realise this tool is not going to solve all the problems. But it is likely to be the first positive thing that may encourage young foreigners to learn Polish,”explains Ośko.

The game will be published in five language versions: Polish, Chinese, Vietnamese, English and Norwegian. However, the new tool is not the only result of the project:

“The Polish kids could at last see that their peers from China or Vietnam were also talented, could paint beautiful pictures, had maths skills and could tell sophisticated stories. They had not had the chance to demonstrate this in regular classes. Further, Polish students happened to be a minority in the groups. They would rush to us crying: I am alone with all these Chinese children, I don’t understand anything, what am I supposed to do? The experience of being in the shoes of foreign peers for a while made a huge impact on the Polish kids,”Ośko adds.