Key facts

Articles

Currently available funding

More information

- Programme website

- Bulgaria country page

- Croatia country page

- Cyprus country page

- Czech Republic country page

- Estonia country page

- Greece country page

- Hungary country page

- Latvia country page

- Lithuania country page

- Malta country page

- Poland country page

- Portugal country page

- Romania country page

- Slovakia country page

- Slovenia country page

- Spain country page

Programme Summary

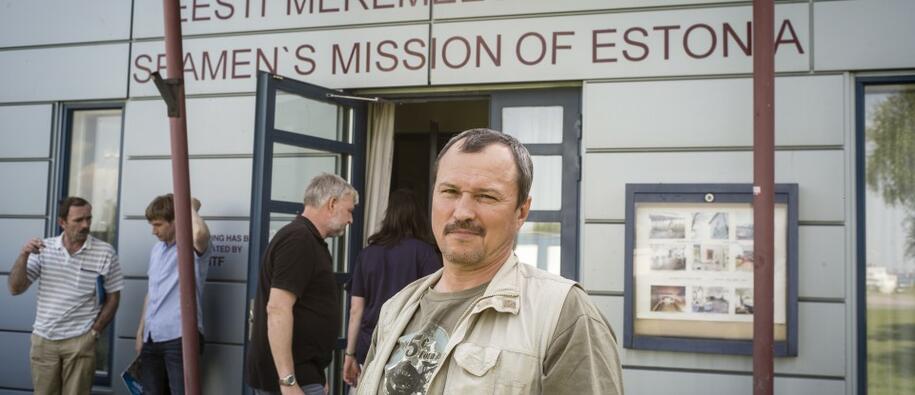

Why was the programme needed? The programme IN22 Global Fund for Decent Work and Tripartite Dialogue aimed to encourage the Nordic Model of tripartite dialogue and decent work agenda in the 13 beneficiary countries of the Norway Grants. In doing so, the programme aimed to contribute to more sustainable socioeconomic development, especially after the unprecedented challenges following by the financial crisis of 2008 which resulted in increased public debts, unemployment and labour market challenges across Europe. The main aims of the programme were the following: • Improved social dialogue and tripartite structures • Enhanced understanding of the importance of decent work • Strengthened bilateral relations between Norway and the beneficiary countries The programme consisted of 52 projects implemented in 13 beneficiary countries in 2014-2015. Each beneficiary country had its specific context and the projects had a great variety of thematic focus. The projects focused on diverse issues of decent work and tripartite dialogue, including pension reforms, minimum wages, transparency and sustainable social policy, decreasing trade union membership and sustaining collective bargaining agreements. Each project was combined with capacity building measures to enhance its impact, its influence on the decision-making and the sustainability of results achieved. The projects were implemented by a variety of project promoters, mainly representing trade union and employers’ organisations in the beneficiary countries. The size of the projects averaged 153,500 euro and ranged from 16,000 euro to 395,000 euro. The administration of the programme was entrusted to a Programme Operator from Norway: Innovation Norway. The programme is complementary to social dialogue activities promoted and implemented by the European Social Fund. What did the programme achieve? The aims of the programme were ambitious, complex and aimed at long-term effect, but they provided ample opportunities for activities which were tailored to the context and targeted at the needs of each beneficiary country. Implementation was at times challenging, because activities were perceived as controversial and because they had to function in different and sometimes difficult socioeconomic environments. The programme was nevertheless well received and attracted keen interest in most of the beneficiary countries. The promoters of the projects in the beneficiary countries found the programme highly relevant for the challenges in their countries. A survey showed that some 90% of project promoters considered that, despite the historical, socioeconomic developments and cultural differences, many sub-elements of the Nordic Model of tripartite dialogue and decent work could be applied in their countries. Moreover, between 84 and 97% of them believe that the projects have a profound effect on the promotion of social dialogue and the understanding of decent work. The results of the programme are not easily quantified in numbers. The following achievements nonetheless give an idea of the activity which took place within the programme: • 150 structures for tripartite dialogue at national, regional or sectoral level were established across the 13 beneficiary countries. • A total of 8,392 people participated in trainings or workshops aimed to raise awareness and enhance the understanding of decent work. • A total of 68 surveys were carried out and analyses were conducted with more than 7,000 interviewees. • A total of 57 agreements were signed. Of these, 51 agreements were on tripartite dialogue and six agreements were on decent work. • 96 social dialogue bodies were established. • 51 best practices on decent work and tripartite dialogue were identified. • Awareness of decent work and tripartite dialogue was also raised by the establishment of 31 web portals, more than 38,000 training materials, guidebooks and leaflets, and some 244 items reported by the media. A total of 333 items were reported by the news media in relation to capacity building on decent work issues. Below are examples of results achieved in each of the beneficiary countries supported. Working jointly, employers’ and trade union organisations from Norway and Bulgaria reached consensus on an increase in the minimum wage determination and issues related to retirement. The concept of labour courts concept was also submitted to broad discussion. In Cyprus, a small project succeeded in establishing a platform involving all main stakeholders, based on the recognition of equal treatment on the labour market and in the workplace. This was considered a proactive move towards more effective communication and regular social dialogue. In the Czech Republic, the programme showed that raising awareness and trust between social partners can lead to win-win situations. The projects led to the signing of a collective agreement in the clothing, textile and leather industry as well as to new provisions concerning disease prevention and rehabilitation, which were incorporated in the Czech Labour Code. They also contributed to the conclusion of the first collective bargaining agreement for the forest industry and assured that provisions for older workers were incorporated into the national Codex of Law. The Nordic Model had a mobilising effect in Croatia. A project led social partners to reach compromise at a tripartite conference and to commit to greater involvement in the decision-making process at national level, with employers focusing on longer-term reforms and unions consolidating its organisational structures and resources. In Estonia, the Nordic Model was a source of inspiration for the first ever signature of a collective agreement on prevention of third party violence, which was signed related to Estonian ports. Projects in Hungary gave impetus to the role of social dialogue by improving dialogue at bipartite level, raising the competence of trade union representatives, establishing networks and signing collective agreements at branch level, including in the water industry. They also secured an agreement at national level on a wage increase in the private sector. In Poland, social partners took joint measures for amending the Labour Code with increased flexibility, parental leave, reconciliation of work and family responsibilities and a new social dialogue legislation. A new law re-constituting the tripartite council was passed in August 2015. This cannot be attributed directly to the programme but, as local promoters stated, “leaders took a lot from the Norwegian Model of social dialogue”. A project in Malta produced a number of research-based recommendations on flexible employment contracts, benefits and risks to employees, and on changes in the Maltese labour market. In Latvia, a consensus decision was reached on tax policies, increased employment and social benefits. In Lithuania, ‘grassroots municipal social dialogue’ entities were established in three municipalities, where they contributed to enhancing the quality of public services, influenced by the Norwegian experience of indexing and assessing service performance. Projects also promoted tripartite dialogue and catalysed collaboration between national and regional tripartite councils on decent work benefits. In Romania, a project produced social dialogue structures in education with the aim of capacity building focusing on health and safety. Awareness raising activities and an information network among social partners were implemented in both the private and public sector. A sustainable factor of the project was the involvement of a large number of civil servants from the Education Ministry. Research carried out under a project in Slovakia led social partners to reach consensus on the quality of the structure of the tripartite dialogue process. The Slovak government accepted an impact assessment of new legislation based on consultation with these social partners. Introducing a system based on Regulatory Impact Assessment – a new approach in the tripartite dialogue (Slovakia). In Slovenia, the projects allowed for a special benefits and a retirement scheme for workers in difficult and unhealthy conditions to be proposed for enactment. Capacity building was a component in all projects. Capacity building on tripartite relations was ensured through 299 workshops, 92 round tables, and more than 6,000 training programmes. On decent work issues, a total of 333 items were reported by the media in relation to capacity building. These results indicate the network of organisations at national and international level which was mobilised. Gender equality was a cross-cutting issue in the programme, in line with gender equality being an integral part of the decent work agenda of the International Labour Organisation (ILO). Gender equality was also an objective in selected projects. One project in Poland (IN22-0006 ‘Superwomen on the labour market’), focused on work-life balance, resulted in recommendations for legislative amendments on reconciling work and family, including recommendations to the Polish Maternity Leave Act which was passed successfully.How did the programme strengthen bilateral relations? The programme improved bilateral relations between Norway and the beneficiary countries. More than half (56%) of the 52 projects were implemented in cooperation with at least one Norwegian partner. A total of 13 Norwegian organisations participated. Of these, 10 were trade unions, two were employer organisations and one was a government ministry. Cooperation with Innovation Norway as Programme Operator contributed to strengthening bilateral relations in projects without a Norwegian partner. The bilateral cooperation showed that the Nordic Model is perceived as a real-life model and a source of inspiration. It also proved that many elements of the model can be applied in the beneficiary countries. The Norwegian partners had considerable experience with international cooperation. They succeeded in establishing common understanding and platform for dialogue, and they took active part in and contributed with extensive experience to project initiation and implementation. The projects included a total of 58 study visits from the beneficiary countries to Norway and 37 visits from Norway to the beneficiary countries. The sharing of experience, ideas and models contributed to the success of most projects. Project reports and a survey confirm that the cooperation between project promoters in the beneficiary countries and their Norwegian partners was fruitful. Some 65% of the interviewees who collaborated with Norwegian partners confirmed that the cooperation had not only contributed to the promotion of bilateral relations but that it had also influenced the capacity of their own organisations. What will be the impact of the programme? Most of the project promoters were representative national social partner organisations, mandated by their constituents to defend their positions. In answering a survey, 87% of the project promoters said that the results of the project could be repeated in the future within their own organisations, and 73% said that they could be replicated in other organisations. Some 70% considered that they will be able to continue the new activities without additional funding. It is expected that the promoters will continue to provide best practices from the projects within the scope of implementing their mandates. The projects have offered potential for both ideas and practices to continue developing after the end of the programme. At national level, the continuation of meaningful social dialogue is largely contextual, depending on the political environment. Still, enhancing the potential of the Nordic Model, through a bottom-up approach, and increasing the volume of good solutions at all levels, are important contributions to lasting change. In many cases, the results of the programme also reached national-level dialogue. In other cases, results at local, regional or sectoral level can be transferred or scaled up to national level. In conclusion, a foundation was established for replicating and continuing meaningful work on social dialogue in the beneficiary countries. The programme influenced social dialogue and tripartite dialogue structures and practices at various levels in the beneficiary countries.