In a colorful hallway in a new department at the children’s hospital in Tallinn, mentally sick children and youth are receiving psychological and psychiatric help. This is where Kathriin (14) and Vlad (16) are. Both struggling with panic attacks and anxiety. Both determined to get better.

“A good place with good people”

16-year-old Vlad started struggling with mental problems at the age of 12, but he wanted to fix himself. After staying at the mental health centre in Tallinn for one week he is more optimistic about receiving help.

“I think this is a good place because there are a lot of good people and medical staff that takes care of us - they are really friendly. I speak Russian and they speak Estonian, I thought it would be a problem, but we are able to communicate,” says Vlad.

In Estonia, more and more children and young people are suffering from mental health problems. In 2015, the rate of newly diagnosed psychiatric cases among children age 0-19, was 1 966 per 100 000, according to the statistics of the Estonian National Institute for Health Development.

With the project ‘Establishing children’s mental health centre’, financed through the Norway Grants, Estonia now aims at improving the quality of mental health services offered to children and youth.

“During the past years we arranged more than hundred workshops training medical staff in different therapeutic methods. We also improved cooperation between preschools, schools, and social welfare specialists to ensure everyone is on the same page. In addition, we gained a new centre with three departments focused on mental illnesses,” says project assistant Kristiina Kongo.

The children’s hospital in Tallinn have established the largest children’s mental health centre in Estonia with 80 staff members.

“I wanted to die”

Vlad is happy to have the possibility to choose music as therapy. He thinks it’s easier to talk to the therapist about his dark thoughts when music is in focus.

“Music is like food, - it gives me energy. I had a long depression, I got panic attacks and thought of committing suicide– my friend told me to get help”, says Vlad.

He is content with the therapeutic advice he has received at the mental health centre.

“My psychologist said: `You don’t have to listen to everything people say about you Vlad! Just listen to what you want, don’t listen to negative people´, it may seem simple, but that advice really helped me,” says Vlad.

In 2014, the suicide rate in Estonia was 18 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants, while the average in the European Union was 11 per 100 000. Lithuania registered by far the highest rate of suicide among the EU Member States, while Estonia had the fifth highest rate, after Latvia, Hungary and Slovenia, according to Eurostat.

Eating disorders and addiction

“The centre offer different therapy methods and advanced diagnostic services - we are finally able to compare ourselves with other countries,” says Kristiina.

The children often struggle with eating disorders, addiction, or behavioral problems.

“A child with behavioral problems is not a bad child; it could be caused by a traumatic childhood or an ADHD-diagnosis,” Kristiina says.

“As parents, there is no topic more important than the health of children.” Read the Estonian Prime Minister Taavi Roivas message during the opening ceremony of the new Tallinn Children’s Mental Health Centre.

“Life can be shitty sometimes”

There is a friendly environment at the Children’s mental health centre in Tallinn. The art room is filled with paintings, colors, and pencils. On the walls, there are colorful traces of a creative therapy session. This is where Kathriin (14) likes to stay.

I have been here for almost one week - this is my second time around. I think it’s a nice place to be when you are exhausted by your own problems. The therapy is great. I have music and art therapy,” says Kathriin.

Her psychologist is strict when she needs to be, but according to Kathriin she believes in her.

“She is not like `everything is going to be okay, ´ - she is honest, like; `yes, life can be shitty sometimes´.”

Right now, 14 885 people have benefited from improved health services in Estonia. Read about the key results here.

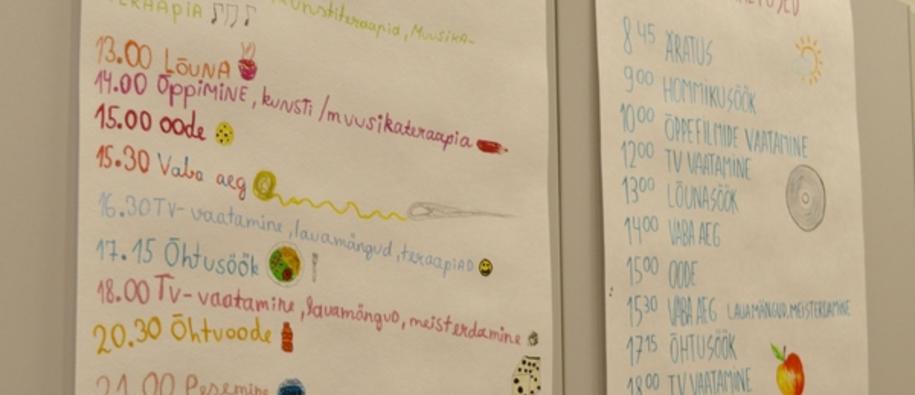

Every day, Kathriin and the other children follow a tight schedule - when to wake up, have breakfast, study, have therapy, and bedtime. Kathriin sees the routines as necessary to make improvements; however, there was a particular advice that helped her avoid panic attacks.

“The best advice I got from my therapist was to chew gum to keep my brain distracted from anxiety, it really helps me. Now I never leave my house without gum,” says Kathriin.

The project 'Establishing children’s mental health centre' is a part of the ‘Public Health Initiatives’ programme with the aim of improving mental health services.

We have many interesting health projects funded by the EEA and Norway Grants. Read about them here:

How did an app and television channel improve the Portuguese health? Read the full story here.

Read about how a perinatal hospice in Poland helps mothers who feel left out of motherhood.